Hemifacial Spasm - What it is and Neurological Treatments Available in Singapore

Hemifacial spasm is a disorder where involuntary muscle twitching occurs on one side of the face. It often begins with twitching around the eye before gradually spreading to other areas of the face, like the cheek and mouth. Less commonly, it can also affect both sides of the face. The spasms occurs due to pressure and irritation on the facial nerve. These frequent spasms are not life threatening, but can be uncomfortable, embarrassing, interfere with social life and significantly impact quality of life.

Hemifacial spasm is more common in women compared to men. We have found that hemifacial spasm occurs more commonly among Asians compared to Caucasians.

Dr Nicolas Kon is a specialist neurosurgeon in Singapore who provides the full range of treatment for hemifacial spasm including medical therapy, injection, and microvascular decompression surgery.

Symptoms of hemifacial spasm

Estimate your severity

Prognosis of hemifacial spasm

Will the spasms go away by themselves?

Is my eye twitching hemifacial spasm?

Well-being and quality of life

Causes of hemifacial spasm

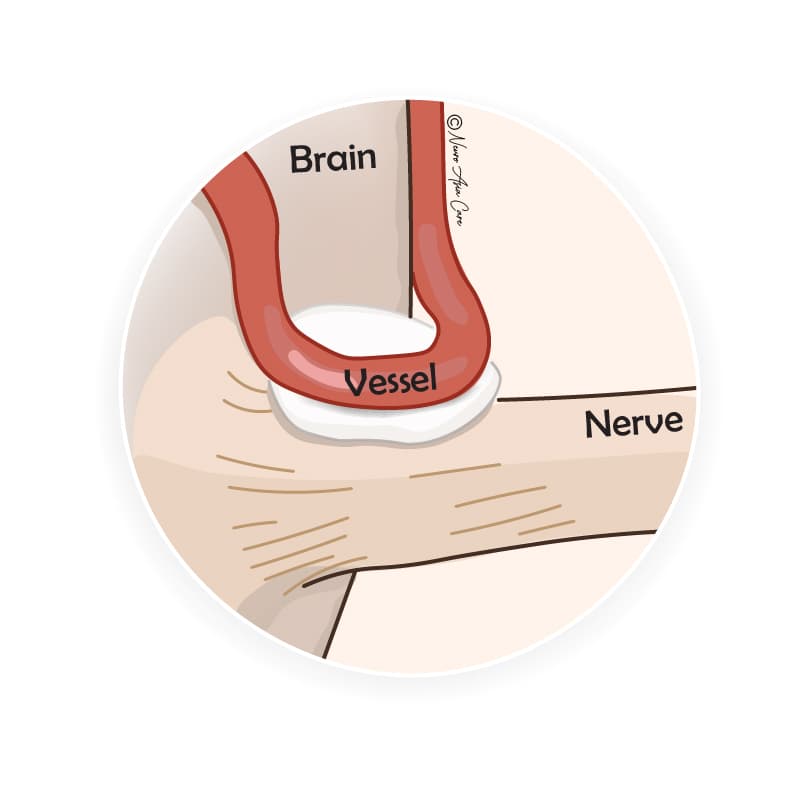

Hemifacial spasm is commonly caused by a compression on the facial nerve - the seventh cranial nerve (CN VII). The reason for the compression is often from a blood vessel loop directly pressing against the nerve. The blood vessel rubs against the nerve in rhythm with the heartbeat, gradually wearing down the nerve’s protective insulation. The "wear and tear" causes the nerve to misfire, generating the abnormal nerve signals that then trigger the muscle spasms.

Less commonly, hemifacial spasms can also be caused by a nerve injury or brain tumour pressing on the facial nerve. Sometimes, no cause can be found.

The cause of hemifacial spasm is similar to that of Trigeminal Neuralgia, a condition caused by abnormal pressure from a blood vessel on the fifth cranial nerve (CN V).

Diagnosis of hemifacial spasm

- Diagnosing hemifacial spasm primarily involves examining the characteristics of the twitches or contractions affecting one side of the face. A detailed patient history about the type, duration, and areas of the spasms can help raise suspicion for this condition. It’s important to consult a specialist experienced in diagnosing hemifacial spasms for an accurate evaluation.

- The Babinski-2 sign helps to distinguish hemifacial spasm from similar conditions like blepharospasm. It is important to look for this sign.

- MRI scan is used to look for blood vessel compressing the nerve or for any tumour compressing the nerve.

- Electromyogram is occasionally also necessary to rule out other conditions such as facial synkinesis.

Treatment of hemifacial spasm

Medication is not considered to be effective.

Hemifacial spasm is initially treated with oral medications or injection of botulinum toxin type A. The oral medications used are baclofen (Lioresal), clonazepam (Rivotril), and carbamazepine (Tegretol). Unfortunately, drugs very often do not work well in this condition and are not considered a main treatment. Many patients also find the side effects of medication outweigh any benefits.

Injection is an effective treatment but needs to be repeated regularly.

Botulinum treatment (Botox) involves injecting small amounts of the toxin into the affected muscles, usually around the eye and cheek. The injections "freeze" the facial muscles by blocking nerve signals.

Botox can be effective for 3 to 6 months, but it is not a permanent solution. The injections will need to be repeated over multiple throughout the year. Over time, the effectiveness of Botox may decrease as the condition progresses. Some people might experience temporary eyelid or facial drooping after the injection. Very rarely, patients may develop neutralising antibodies to Botox and become resistant to the treatment. The illustration below shows the most frequently treated muscles in hemifacial spasm, where the red circles indicate the typical injection sites.

Microvascular decompression (MVD) is an effective treatment that is performed once.

A common procedure used by our neurosurgeon to treat severe hemifacial spasm is microvascular decompression. It is the most appropriate treatment for some patients, especially those who fail or cannot tolerate repeated botox injections.

In this procedure (illustrated in the figures below), a small opening is made in the skull. A piece of Teflon padding is carefully placed between the nerve and blood vessel to prevent further compression and stop the electrical misfiring that causes spasms.

This is a microsurgery that involves making a key-hole opening behind the ear, just large enough to access the facial nerve. The surgery is performed under high magnification using a surgical microscope and endoscope. The Teflon cushion that is placed between the nerve and the blood vessel is about the size of a grain of rice.

Depending on the anatomy of the compression, other surgical method will be used such as the sling technique which avoid the use of a Teflon cushion. Additional advanced surgical techniques such as image guidance and intra-operative neuromonitoring further ensure safe and efficient surgery.

Recovery after MVD surgery

As this procedure is minimally invasive (keyhole), the time to recovery is short. Most patients will return to their regular activities within one to two weeks after surgery.

Good results with life-long benefits

By releasing the irritation on the nerve, the root cause of the problem is immediately relieved. MVD can permanently resolve hemifacial spasm in most patients. Patients often experience relief immediately after surgery, while others will notice resolution over the following weeks as the nerve heals.

Approximately 90% to 95% of patients find lasting relief after MVD surgery. Unlike treatments that only manage symptoms, MVD surgery provides a lasting cure, meaning most patients will not require additional treatment for their condition - this can be truly life-changing, offering far more than mere relief.

Summary

References

2. Park CK et al. Clinical application of botulinum toxin for hemifacial spasm. Life. 2023;13(8):1760